Getty Images

Getty ImagesIndia’s Election Commission (ECI), one of the most trusted public institutions in the world’s largest democracy, is facing a test of its credibility.

Over the past few weeks, it has fielded a string of allegations from the opposition, ranging from voter fraud and manipulation to inconsistencies in electoral rolls. It has denied all of these.

Opposition leaders, who have held massive protests against the ECI in recent days, said they were considering an impeachment motion to remove the chief election commissioner from his position. They hadn’t filed the motion by Thursday, the last day of the monsoon session of parliament, and currently don’t have the numbers to see it through.

Meanwhile, Rahul Gandhi, the leader of India’s main opposition party Congress, has launched a 16-day, 1,300km (807 miles) march – known as the Voter Adhikar Yatra (Voter Rights March) – in Bihar state to protest against the ECI, marking a dramatic escalation in the political fight. Bihar, set to vote in a key state election later this year, has been in the middle of a heated controversy over a recent revision of electoral rolls.

Gandhi first made the allegations of vote theft in August, accusing the ECI of colluding with the governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) to rig the 2024 general elections.

Using granular data from the ECI’s own records, he alleged that a parliamentary constituency in the southern state of Karnataka had more than 100,000 fake voters, including duplicate voters, invalid addresses and bulk registrations at single locations.

The ECI has repeatedly called the claims “false and misleading”. And the BJP has strongly denied these allegations, with leader Anurag Thakur saying the Congress and the opposition had come together to make these “baseless claims” because they were anticipating a loss in Bihar.

Gandhi’s press conference was held as the controversy in Bihar was raging.

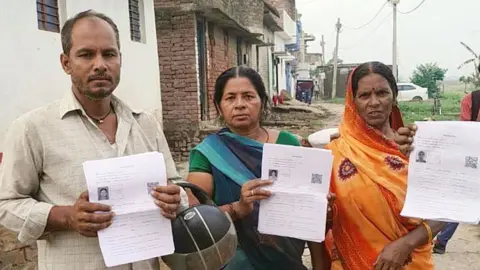

The Special Intensive Revision (SIR) happened between June and July, with the ECI saying its representatives visited all of Bihar’s 78.9 million voters for verification.

The ECI says this was done to update the voter lists after more than 20 years, but opposition leaders say the process may have disenfranchised tens of thousands of people, especially migrants, because of the haste with which it was conducted and the onerous documentation required as proof.

After a draft of the updated list was published on 1 August, several reports, including by the BBC, highlighted errors in the count, such as the wrong gender and photos assigned against people’s names, and dead voters on the rolls.

The new draft rolls have 72.4 million names – 6.5 million fewer than before, with the commission saying the omissions include duplicate, deceased and migrant voters. Those who believe their names were wrongly struck off have been given until 1 September to appeal.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesMeanwhile, criticism also intensified over the manner in which the ECI published the names of the 6.5 million people that were excluded from the draft rolls.

Opposition parties questioned why the commission was putting up scanned physical copies, rather than machine-readable lists of omitted voters, which could be independently verified by analysts and political parties.

Eventually, India’s top court told the ECI to publish a searchable list of voters and also state the reasons for their exclusion.

The court’s intervention highlighted the ECI’s “procedural failures” and must be seen as a “rap on the knuckles”, an editorial in the leading Hindu newspaper said.

Amid the mounting criticism, ECI held a rare weekend press conference on17 August to address some of the allegations.

“If you use terms like vote theft and mislead citizens, then what else would you call this, other than an insult to India’s constitution?” Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar said, referring to Gandhi’s allegations.

He cited a 2019 Supreme Court judgment to say the opposition’s demand for machine-readable voter lists could impinge on people’s privacy.

He also demanded that Gandhi either give an affidavit under oath proving his allegations, or apologise to the nation for his remarks.

But instead of putting the matter to rest, the statements sparked further outrage, with some opposition politicians accusing Kumar of either avoiding answering specific questions or providing unsatisfactory explanations.

Pawan Khera of the Congress party told BBC Hindi that Kumar’s “adversarial tone” at the press conference made it seem “as if a BJP leader was speaking”.

Experts say that on their own, the allegations by Gandhi, or the fact that millions of new voters have been added or removed from the rolls in Bihar, don’t prove any wrongdoing.

“When the voter list is intensively verified, such large differences in numbers are bound to occur,” former chief election commissioner N Gopalaswami told BBC Tamil.

Mr Gopalaswami added that when the electoral roll for the southern state of Karnataka was revised in 2008, some 5.2 million voters were removed, with nearly one million people applying to be added again.

He also agreed with the ECI’s demand for a signed affidavit by Gandhi, saying that responding to allegations without a written complaint sets a bad precedent for the institution.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut with Gandhi’s voter rights march under way and the Bihar elections looming, the issue is unlikely to die down.

“Whatever the Election Commission says, the opposition will definitely make it an issue in the upcoming Bihar elections,” senior journalist Smita Gupta told BBC Hindi.

In the meantime, there are larger concerns at play about the impact of all of this on the public’s trust in the ECI.

“The trust the ECI once commanded almost unquestioningly is now under greater public scrutiny,” former chief election commissioner SY Quraishi wrote in the Indian Express newspaper.

He added that while the “procedural architecture for transparency in elections remains in place… the perception of impartiality is as important as its reality. Reinforcing this trust is as crucial as ensuring technical accuracy”.

According to a survey published this month by Lokniti, a research programme at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), however, trust in the ECI has dropped sharply.

The agency’s chief Sanjay Kumar has been separately in the crosshairs of the ECI and the BJP after he issued an apology for sharing wrong data on voter turnout in the state of Maharashtra, but its findings in other states point to a rising trust deficit with the ECI.

In all the six states surveyed by CSDS in 2025, the number of people who had no trust in the EC had risen sharply from 2019 – In Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, it rose from 11% to 31% in the period.

This systematic erosion, Mr Kumar told The Wire news portal, “should be a big worry” for the commission.

“It is not only the trust of the opposition which has gone down, it is also the trust among the people that has come down. The data clearly indicates that,” Mr Kumar said.

Follow BBC News India on Instagram, YouTube, X and Facebook.