Luke MintzBBC News

Luke MintzBBC News BBC

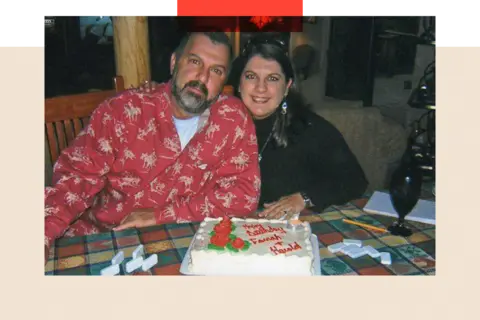

BBCHarold Dillard was 56 when he was diagnosed with an aggressive cancer around his abdomen in November 2009. Within weeks the former car mechanic and handyman – a Texan “Mr Fix It” type who wore a cowboy hat and jeans nearly every day – was in end-of-life hospice care.

In his final days, Mr Dillard was visited at the hospice by a company called Bio Care. They asked if he might like to donate his body to medical science, where it could be used by doctors to practise knee replacement surgery. The company would cremate the parts of his body that weren’t used and return his ashes free of charge.

“His eyes lit up,” his daughter, Farrah Fasold, remembers. “He viewed that as lessening the burden on his family. Donating his body was the last selfless thing he could do.”

Mr Dillard died on Christmas Eve, and within hours, a car from Bio Care pulled up outside the hospice and drove his body away.

A few months later, his daughter received a call from the police. They had found her father’s head.

At the company’s warehouse, police say they found more than 100 body parts belonging to 45 people. “All of the bodies appeared to have been dismembered by a coarse cutting instrument, such as a chainsaw,” a detective wrote at the time.

Ms Fasold says she imagined her father’s body would be handled with respect – but instead it was “mutilated”, she believes.

“I would close my eyes at night and see huge red tubs filled with body parts. I had insomnia. I wasn’t sleeping.”

The company said at the time through a lawyer that they denied mistreating bodies. The firm no longer exists, and its former owners could not be reached for comment.

This was Ms Fasold’s first introduction to the world of so-called body brokers: private companies that acquire corpses, dissect them, and then sell the limbs for a profit, often to medical research centres.

For critics, the industry represents a modern form of grave-robbing. Others argue that body-donation is essential for medical research and that private companies are simply filling a gap left by universities, who consistently fail to acquire enough dead bodies to support their education and research programmes.

Although Ms Fasold didn’t realise it at the time, her father’s case sheds light on an emotion-fuelled debate that cuts to the centre of our ideas about life, and what it means to have a dignified death.

The body business

Since at least the 19th Century, when the teaching of medicine expanded, some scientifically-minded people have rather liked the idea that their corpse could be used to train doctors.

Brandi Schmitt is director of the anatomical donation programme at the University of California, a popular destination for people wishing to bequeath their bodies. She says last year they received 1,600 “whole-body donations”, and they have a list of almost 50,000 living people who have already registered to do so.

Often, body-donation is driven by simple altruism, she says: “A lot of people are either educated or interested in education.”

But financial factors come into play too. Funerals are expensive, Ms Schmitt says; many are tempted by the prospect of their body being taken away for free.

Like most medical schools, the University of California does not profit from its body-donation programme, and it has strict guidelines for how corpses – or cadavers, as they are known medically – should be handled.

But in recent decades, something more controversial has emerged in the US: a network of for-profit businesses that act as middlemen, acquiring bodies from individuals, dissecting them, and then selling them on. They are widely nicknamed body brokers, though the firms call themselves “non-transplant tissue banks”.

Some of their customers are universities, which use cadavers to train doctors. Others are medical engineering firms, which use limbs to test products like new hip implants.

The for-profit body part trade is effectively outlawed in the UK and other European countries, but looser regulation in the US has allowed the trade to flourish.

The largest investigation of its kind – conducted by Reuters journalist Brian Grow, in 2017 – identified 25 for-profit body broking companies in the US. One of them earned $12.5m (£9.3m) over three years from the body-part business.

Some of those firms are broadly respected, and claim to follow rigorous ethical guidelines. Others have been accused of disrespecting the dead and exploiting vulnerable people in grief.

A global trade

The trade has grown because of a gap in US regulation, says Jenny Kleeman, who spent years researching the topic for her book, The Price of Life.

Whilst the UK’s Human Tissue Act makes it illegal in almost all cases to profit from a body part, no comparable law exists in the US. Technically, the US’s Uniform Anatomical Gift Act bans the sale of human tissue – but the same law allows you to charge a “reasonable amount” for the “processing” of a body part.

These loose laws have turned the US into a global exporter of cadavers. In her book, Kleeman found that one of the largest US players shipped body parts to more than 50 countries, including the UK.

“In many countries, there is a shortfall of donations,” Ms Kleeman says. “And where they can get bodies is from America.”

There is no formal register of brokers, and official statistics are hard to find. But Reuters calculated that, from 2011 to 2015, private brokers in the US received at least 50,000 bodies, and distributed more than 182,000 body parts.

‘Bodies of the state’

For some, private body brokers represent the very worst sort of ambulance-chasing greed.

In his Reuters investigation, Mr Grow found cases of brokers becoming “intertwined with the American funeral industry” via arrangements in which funeral homes introduce brokers to relatives of the recently-deceased. In return, the home received a referral fee, sometimes exceeding $1,000 (£750).

Horror stories are easy to find – and because of the US’s light regulation, there’s often no legal recourse when things go wrong.

After her run-in with Bio Care, Ms Fasold hoped for a criminal prosecution. As well as the fact that her father’s limbs may have been cut with a chainsaw, she was unhappy about a package she had received in the post, in a zip-lock bag, which the company claimed was her father’s ashes. She says the contents did not look or feel like human ashes.

Bio Care’s owner was initially charged with fraud, but the charge was later withdrawn because prosecutors could not prove an intent to deceive.

Increasingly desperate, Ms Fasold contacted the local district prosecutor. But she was told that Bio Care had not broken any state criminal laws.

Equally as controversial are “bodies of the state” donations – when a homeless person dies on the street, or somebody dies in hospital without known next-of-kin, and their corpse is donated to science.

In theory, county officials first try to find relatives; only if they cannot locate anyone is the body given away.

But the BBC has heard that this may not always happen. Last year, Tim Leggett was scrolling a news app at his home in Texas when he found a list of local people whose bodies had been used in this way. He was shocked to see the name of his older brother, Dale, a forklift truck-operator who had died of respiratory failure a year earlier.

His brother’s body was used by a for-profit medical education company to train anaesthesiologists. It was one of more than 2,000 unclaimed bodies given to the University of North Texas Health Science Center between 2019 and 2024, under agreements with the Dallas and Tarrant counties.

“I was angry,” Mr Leggett says. “He would not want to be an object of discussion, or [to have] people pointing at him.”

His brother was a quiet man who mostly “just wanted to be left alone”, Mr Leggett remembers, and his aversion to technology made it difficult to stay in touch. Still, Mr Leggett says his brother was a human, like anyone else, who deserved dignity in death.

“He liked Marvel comic books; he had a cat that he named Cat,” he remembers.

In a statement to the BBC, the University of North Texas Health Science Center gave its “deepest apologies” to the affected families, and said it was “refocusing” its programme on education and “improv[ing] the quality of health for families and future generations”. Since the story first emerged last year, they said, they have fired staff who oversaw the programme.

Unfairly villainised?

But horror stories like these aside, others point out that body donation plays a crucial role in scientific discovery.

Ms Schmitt of the University of California says that at the most basic level, bodies are used to teach doctors, or for surgeons to practise complicated operations. Often, it’s the first time a medical student works with real flesh and blood – an experience that can’t be replicated from a textbook.

“Those students will go on to help people,” she says.

Then there are the cadavers used to help engineer new treatments. Ms Schmitt points to a number of technologies that were only developed, she says, after being tested on bodies. These include knee and hip replacements, robotic surgery, and pacemakers.

Bloomberg via Getty Images

Bloomberg via Getty ImagesAnd some of the private brokers say they are being unfairly villainised. Kevin Lowbrera, who works for one of the big “body broking” companies, says its accreditation by the American Association of Tissue Banks means it has to follow guidelines determining how cadavers are treated and stored. Accreditation is voluntary – seven companies have signed up – and a private broker doesn’t need it to operate legally.

The problem is not with honest companies like his, Mr Lowbrera says – it is with the rogue players. “There are still programmes out there that are not accredited. I tell people all the time, stay away from them,” he says.

It would be wrong to regulate his whole industry out of existence, he says, because of some bad apples.

Beyond the for-profit trade?

Virtually everyone I speak to – on all sides of the debate – thinks that more regulation in the US is needed.

So, what could that look like?

Ms Schmitt, of the University of California, suggests the US could perhaps follow European countries and ban for-profit body broking.

She says there are some “legitimate costs” that come with processing a body – like spending on transport, and preservative chemicals. It’s reasonable for companies to charge for these, she says. But the idea of actually making a profit makes many feel squeamish. “The ability to sell or profit from human remains I think complicates the altruistic idea of donating for education,” she says.

She suggests the US could emulate its own policy on organ donation – which is governed by the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, and prohibits the sale of organs.

But the author Ms Kleeman says that if the US banned for-profit body donation tomorrow, there simply wouldn’t be enough cadavers to go around.

“If you don’t want there to be a trade in these body parts, we need to get a way of more people donating altruistically,” she says.

She urges universities to launch more robust promotional campaigns, asking directly for body donations. “There isn’t the same public awareness campaign as there is for organ donation, for example.”

Once this shortage is addressed, she says, then the US could ban for-profit donation.

It’s also possible that advances in virtual reality (VR) technology mean that cadavers simply won’t be needed in the future. A trainee doctor could simply put on a headset and practice on a computer-generated patient.

In 2023, Case Western Reserve University became one of the first medical schools in the United States to remove human bodies from its training programme, and replace them with VR models.

Real human bodies preserve the “body’s colours and textures, [which] can make it difficult to discern, say, a nerve from a blood vessel”, Mark Griswold, a professor at the school, told the website Lifewire at the time. In contrast, their computer programme “gives students a crystal clear 3D map of these anatomical structures and their relationships to each other”, he said.

But Ms Kleeman says that, in general, VR technology is not yet good enough to replicate practicing on a cadaver.

For the time being, it seems, there will remain a demand for human bodies – as well as money to be made.

Additional reporting: Jacob Dabb

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.