BBC News Climate and Science

Heather Hamilton / @cornwallunderwater

Heather Hamilton / @cornwallunderwaterThe UK’s seas have had their warmest start to the year since records began, helping to drive some dramatic changes in marine life and for its fishing communities.

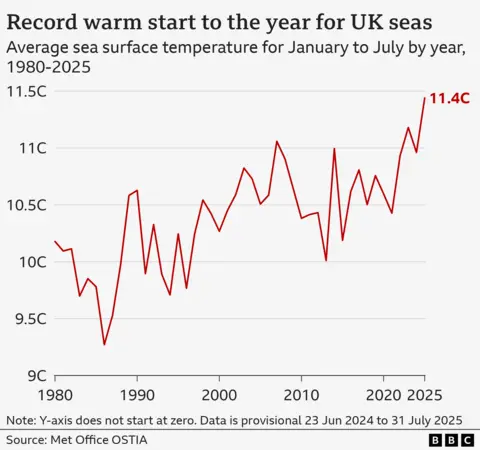

The average surface temperature of UK waters in the seven months to the end of July was more than 0.2C higher than any year since 1980, BBC analysis of provisional Met Office data suggests.

That might not sound much, but the UK’s seas are now considerably warmer than even a few decades ago, a trend driven by humanity’s burning of fossil fuels.

That is contributing to major changes in the UK’s marine ecosystems, with some new species entering our seas and others struggling to cope with the heat.

Scientists and amateur naturalists have observed a remarkable range of species not usually widespread in UK waters, including octopus, bluefin tuna and mauve stinger jellyfish.

The abundance of these creatures can be affected by natural cycles and fishing practices, but many researchers point to the warming seas as a crucial part of their rise.

“Things like jellyfish, like octopus… they are the sorts of things that you expect to respond quickly to climate change,” said Dr Bryce Stewart, a senior research fellow at the Marine Biological Association in Plymouth.

“It’s a bit like the canary in the coal mine – the sorts of quite extraordinary changes we’ve seen over the last few years really do indicate an ecosystem under flux,” he added.

Harry Polkinghorne, a keen 19-year-old angler, described how he regularly sees bluefin tuna now, including large schools of the fish in frantic feeding frenzies.

“It’s just like watching a washing machine in the water,” he said. “You can just see loads of white water, and then tuna fins and tuna jumping out.”

@TheFalAnglers

@TheFalAnglersBluefin tuna numbers have been building over the past decade in south-west England for a number of reasons, including warmer waters and better management of their populations, Dr Stewart explained.

Heather Hamilton, who snorkels off the coast of Cornwall virtually every week with her father David, has swum through large blooms of salps, a species that looks a bit like a jellyfish.

They are rare in the UK, but the Hamiltons have seen more and more of these creatures in the last couple of years.

“You’re seeing these big chains almost glowing slightly like fairy lights”, she said.

“It just felt very kind of out of this world, something I’ve never seen before.”

Heather Hamilton / @cornwallunderwater

Heather Hamilton / @cornwallunderwaterBut extreme heat, combined with historical overfishing, is pushing some of the UK’s cold-adapted species like cod and wolf-fish to their limits.

“We’re definitely seeing this shift of cooler water species moving north in general,” said Dr Stewart.

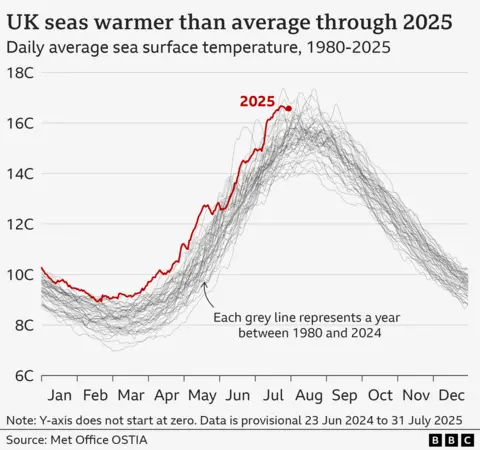

Marine heatwave conditions – prolonged periods of unusually high sea surface temperatures – have been present around parts of the UK virtually all year.

Some exceptional sea temperatures have also been detected by measurement buoys off the UK coast, known as WaveNet and run by the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas).

And the record 2025 warmth comes after very high sea temperatures in 2023 and 2024 too.

The Met Office says its data from the end of June 2024 to now is provisional and will be finalised in the coming months, but this usually results in only very minor changes.

“All the way through the year, on average it’s been warmer than we’ve really ever seen [for the UK’s seas],” said Prof John Pinnegar, the lead adviser on climate change at Cefas.

“[The seas] have been warming for over a century and we’re also seeing heatwaves coming through now,” he added.

“What used to be quite a rare phenomenon is now becoming very, very common.”

Like heatwaves on land, sea temperatures are affected by natural variability and short-term weather. Clear, sunny skies with low winds – like much of the UK had in early July – can heat up the sea surface more quickly.

But the world’s oceans have taken up about 90% of the Earth’s excess heat from humanity’s emissions of planet-warming gases like carbon dioxide.

That is making marine heatwaves more likely and more intense.

“The main contributor to the marine heatwaves around the UK is the buildup of heat in the ocean,” said Dr Caroline Rowland, head of oceans, cryosphere and climate change at the Met Office.

“We predict that these events are going to become more frequent and more intense in the future” due to climate change, she added.

With less of a cooling sea breeze, these warmer waters can amplify land heatwaves, and they also have the potential to bring heavier rainfall.

Hotter seas are also less able to absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, which could mean that our planet heats up more quickly.

The sea warmth is already posing challenges to fishing communities.

Ben Cooper has been a fisherman in Whitstable on the north Kent coast since 1997, and relies heavily on the common whelk, a type of sea snail.

But the whelk is a cold-water species, and a marine heatwave in 2022 triggered a mass die-off of these snails in the Thames Estuary.

“Pretty much 75% of our earnings is through whelks, so you take that away and all of a sudden you’re struggling,” explained Mr Cooper.

Philip Haupt / Kent & Essex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation Authority

Philip Haupt / Kent & Essex Inshore Fisheries and Conservation AuthorityBefore the latest heatwave, the whelks had started to recover but he said the losses had forced him to scale back his business.

Mr Cooper recalled fishing trips with his father in the 1980s. Back then, they would rely on cod.

“We lost the cod because basically the sea just got too warm. They headed further north,” he said.

The precise distribution of marine species varies from year to year, but researchers expect the UK’s marine life to keep changing as humans continue to heat up the Earth.

“The fishers might in the long term have to change the species that they target and that they catch,” suggested Dr Pinnegar.

“And we as consumers might have to change the species that we eat.”

Additional reporting by Becky Dale and Miho Tanaka