BBC News, Sydney

Australian Museum

Australian MuseumIn 1943, a camouflaged ship set off from Australia to England carrying top secret cargo – a single young platypus.

Named after his would-be owner, UK prime minister Winston Churchill, the rare monotreme was an unprecedented gift from a country desperately trying to curry favour as World War Two expanded into the Pacific and arrived on its doorstep.

But days out from Winston’s arrival, as war raged in the seas around him, the puggle was found dead in the water of his specially made “platypusary”.

Fearing a potential diplomatic incident, Winston’s death – along with his very existence – was swept under the rug.

He was preserved, stuffed and quietly shelved inside his name-sake’s office, with rumours that he died of Nazi-submarine-induced shell-shock gently whispered into the ether.

The mystery of who, or what, really killed him has eluded the world since – until now.

Two Winstons and a war

The world has always been fascinated by the platypus. An egg-laying mammal with the face and feet of a duck, an otter-shaped body and a beaver-inspired tail, many thought the creature was an elaborate hoax; a taxidermy trick.

For Churchill, an avid collector of rare and exotic animals, the platypus’s intrigue only made him more desperate to have one – or six – for his menagerie.

And in 1943 he said as much to the Australian foreign minister, H.V. ‘Doc’ Evatt.

In the eyes of Evatt, the fact that his country had banned the export of the creatures – or that they were notoriously difficult to transport and none had ever survived a journey that long – were merely challenges to overcome.

Australia had increasingly felt abandoned by the motherland as the Japanese drew closer and closer – and if a posse of platypuses would help Churchill respond more favourably to Canberra’s requests for support, then so be it.

Conservationist David Fleay – who was asked to help with the mission – was less amenable.

“Imagine any man carrying the responsibilities Churchill did, with humanity on the rack in Europe and Asia, finding time to even think about, let alone want, half-a-dozen duckbilled platypuses,” he wrote in his 1980 book Paradoxical Platypus.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn Mr Fleay’s account, he managed to talk the politicians down from six platypuses to one, and young Winston was captured from a river near Melbourne shortly after.

An elaborate platypusary – complete with hay-lined burrows and fresh Australian creek water – was constructed for him; a menu of 50,000 worms – and duck egg custard as a treat – was prepared; and an attendant was hired to wait on his every need throughout the 45-day voyage.

Across the Pacific, through Panama Canal and into the Atlantic Ocean Winston went – before tragedy struck.

In a letter to Evatt, Churchill said he was “grieved” to report that the platypus “kindly” sent to him had died in the final stretch of the journey.

“Its loss is a great disappointment to me,” he said.

The mission’s failure was kept secret for years, to avoid any public outcry. But eventually, reports about Winston’s demise would begin popping up in newspapers. The ship had encountered a German U-boat, they claimed, and the platypus had been shaken to death amid a barrage of blasts.

Australian Museum

Australian Museum“A small animal equipped with a nerve-packed, super sensitive bill, able to detect even the delicate movements of a mosquito wriggler on stream bottoms in the dark of night, cannot hope to cope with man-made enormities such as violent explosions,” Mr Fleay wrote, decades later.

“It was so obvious that, but for the misfortunes of war, a fine, thriving, healthy little platypus would have created history in being number one of its kind to take up residence in England.”

Mystery unravelled

“It is a tempting story, isn’t it?” PhD student Harrison Croft tells the BBC.

But it’s one that has long raised suspicions.

And so last year, Mr Croft embarked on his own journey: a search for truth.

Accessing archives in both Canberra and London, the Monash University student found a bunch of records from the ship’s crew, including an interview with the platypus attendant charged with keeping Winston alive.

“They did a sort of post-mortem, and he was very particular. He was very certain that there was no explosion, that it was all very calm and quiet on board,” Mr Croft says.

Renee Nowytarger/University of Sydney

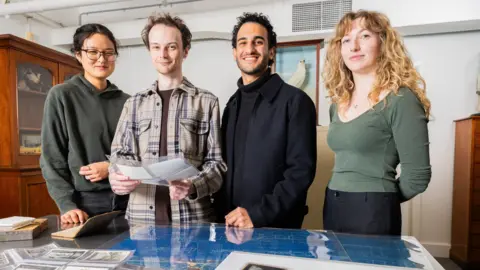

Renee Nowytarger/University of SydneyA state away, another team in Sydney was looking into Winston’s life too. David Fleay’s personal collection had been donated to the Australian Museum, and staff all over the building were desperate to know if it held answers.

“You’d ride in the lifts and some doctor from mammalogy… [would ask] ‘what archival evidence is there that Winston died from depth charge detonations?'” the museum’s archive manager Robert Dooley tells the BBC.

“This is something that had intrigued people for a long time.”

With the help of a team of interns from the University of Sydney, they set about digitising all of Fleay’s records in a bid to find out.

Renee Nowytarger/University of Sydney

Renee Nowytarger/University of SydneyEven as far back as the 1940s, people knew that platypuses were voracious eaters. Legend of the species’ appetite was so great that the UK authorities drafted an announcement offering to pay young boys to catch worms and deliver them to feed Winston upon his arrival.

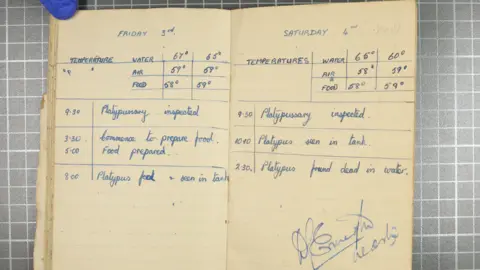

In the platypus attendant’s logbook, the interns found evidence that his rations en route were being decreased as some of the worms began to perish.

But it was water and air temperatures, which had been noted down at 8am and 6pm every day, that held the key to solving the mystery.

These readings were taken at two of the cooler points of the day, and still, as the ship crossed the equator over about a week, the recorded temperatures climbed well beyond 27C – what we now know is the safe threshold for platypus travel.

With the benefit of hindsight – and an extra 80 years of scientific research into the species – the University of Sydney team determined Winston was essentially cooked alive.

While they can’t definitively rule out the submarine shell-shock story, they say the impact of those prolonged high temperatures alone would have been enough to kill Winston.

Australian Museum

Australian Museum“It’s way easier to just shift the blame on the Germans, rather than say we weren’t feeding it enough, or we weren’t regulating its temperature correctly,” Ewan Cowan tells the BBC.

“History is totally dependent on who’s telling the story,” Paul Zaki adds.

Platypus diplomacy goes extinct

Not to be dissuaded by its initial attempt at platypus diplomacy, Australia would try again in 1947.

High off the achievement of successfully breeding a platypus in captivity for the first time – a feat that wouldn’t be replicated for another 50 years – Mr Fleay convinced the Australian government to let the Bronx Zoo have three of the creatures in a bid to deepen ties with the US.

Unlike Winston’s secret journey across the Pacific, this voyage garnered huge attention. Betty, Penelope and Cecil docked in Boston to much fanfare, before the trio was reportedly escorted via limousine to New York City, where Australia’s ambassador was waiting to feed them the ceremonial first worm.

Betty would die soon after she arrived, but Penelope and Cecil quickly became celebrities. Crowds clamoured for a glimpse of the animals. A wedding was planned. The tabloids obsessed over their every move.

Australian Museum

Australian MuseumPlatypus are solitary creatures, but New York had been promised lovers. And while Cecil was lovesick, Penelope was apparently sick of love. In the media, she was painted as a “brazen hussy”, “one of those saucy females who like to keep a male on a string”.

Until 1953 that is, when the pair had a four-day fling – rather upsettingly described as “all-night orgies of love” – fuelled by “copious quantities of crayfish and worms”.

Alas, Penelope soon began nesting, and the world excitedly awaited her platypups, which were to be a massive scientific milestone – only the second bred in captivity, and the first outside Australia.

After four months of princess treatment and double rations for Penelope, zookeepers checked on her nest in front of a throng of excited reporters.

But they found no babies – just a disgruntled-looking Penelope, who was summarily accused of faking her pregnancy to secure more worms and less Cecil.

“It was a whole scandal,” Mr Cowan says – one from which Penelope’s reputation never recovered.

Years later, in 1957, she would vanish from her enclosure, sparking a weeks-long search and rescue mission which culminated in the zoo declaring her “presumed lost and probably dead”.

A day after the hunt for Penelope was called off, Cecil died of what the media diagnosed as a “broken heart”.

Laid to rest with the pair was any real future for platypus diplomacy.

Though the Bronx Zoo would try to replicate the exchange with more platypuses in 1958, the finnicky beasts lasted under a year, and Australia soon tightened laws banning their export. The only two which have left the country since have lived at the San Diego Zoo since 2019.