Hazel ShearingEducation correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPupils in England who missed school during the first week back in September 2024 were more likely to be absent for large parts later in the year, figures suggest.

More than half (57%) of pupils who were partially absent in week one became “persistently absent” – missing at least 10% of school, according to government data first seen by the BBC.

By contrast, of pupils who fully attended the first week, 14% became persistently absent.

Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said schools and parents should “double down” to get children in at the start of the 2025 term, which is this week for most English schools.

The Conservatives said Labour’s Schools Bill had dismantled a system that had “driven up standards for decades”.

A head teachers’ union said more support was needed “outside of the school gates” to boost attendance.

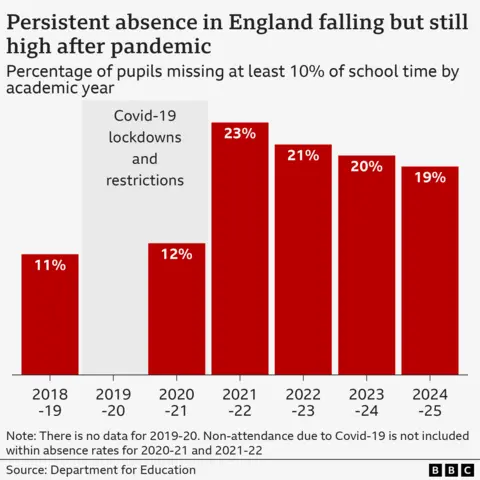

Schools have always grappled with attendance issues, but they became much worse after the pandemic in 2020 and schools closed to most pupils during national lockdowns.

Attendance has improved since, but it remains a bigger problem than before Covid.

Overall, about 18% of pupils were persistently absent in the 2024-25 school year, down from a peak of 23% in 2021-22 but higher than the pre-Covid levels of about 11%.

The Department for Education (DfE) said the data from the first week of the 2024-25 school year showed the start of term was “critical” for tackling persistent absence.

Karl Stewart, head teacher at Shaftesbury Junior School in Leicester, said his school’s attendance rates were higher than average and but there was a “definite dip” in the two years after Covid.

“I get why. Some of that wasn’t necessarily parents not wanting to send them in. It was because either they had got Covid or other things, they were saying, ‘We’ll just keep them off now to be sure’,” he said.

The school has incentives like awards and class competitions to keep absence rates down, and Mr Stewart said attendance had more or less returned to pre-Covid levels.

“When we have the children in every day the results are just better,” he said.

“If you’re here, that gives you more time for your teacher to notice you, for us to see all that good behaviour [and] that really hard work – and that’s what we want.”

But, like lots of schools, he said some parents still took their children on unauthorised term-time holidays to make the most of cheaper costs.

Others, he said, have taken children for medical treatments overseas to avoid NHS waiting lists.

The education secretary said that while attendance improved last year, absence levels “remain critically high, putting at risk the life chances of a whole generation of young people”.

“Every day of school missed is a day stolen from a child’s future,” Phillipson said.

“As the new term kicks off, we need schools and parents to double down on the energy, the drive and the relentlessness that’s already boosted the life chances of millions of children, to do the same for millions more.”

Parents can be fined upwards of £80 if their child misses five days of school without permission. Last year, a record number of fines for unauthorised family holidays were issued in England.

Phillipson told BBC Breakfast that fines remained “an important backstop within the system”.

“It’s not just about our own children, but the impact it has on the whole class – if teachers are having to spend time covering work they’ve already done, it is disruptive,” she said.

But the education secretary stressed that schools were asked to take a “support-first” approach and work with parents where there were wider issues affecting a pupil’s attendance.

The DfE said 800 schools were set to be supported by regional school improvement teams – through attendance and behaviour hubs.

These hubs are made up of 90 exemplary schools which will offer support to improve struggling schools through training sessions, events and open days.

It said it had appointed the first 21 schools that will lead the programme.

However, Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, said attendance hubs were not a “silver bullet” and a more “strategic approach” was needed.

“I think the government has worked really hard to improve attendance and it continues to be a priority for them, but there’s certainly more to do,” he told the BBC.

“So many of the challenges that [school leaders] are facing come from beyond the school gates – children suffering with high levels of anxiety, issues around mental health.”

He said school leaders wanted quicker access to support for those pupils and specialist staff in schools, but pupils also needed “great role models” in the community through youth clubs and volunteer groups.

Shadow education secretary Laura Trott said: “Behaviour and attendance are two of the biggest challenges facing schools and it’s about time the government acted.”

She added: “There must be clear consequences for poor behaviour not just to protect the pupils trying to learn, but to recognise when mainstream education isn’t the right setting for those causing disruption.”

Additional reporting by Nathan Standley