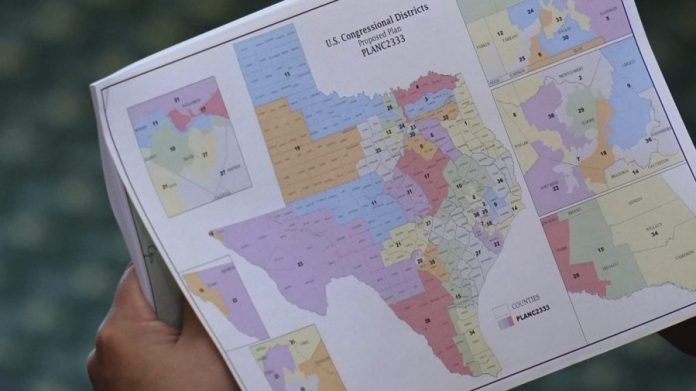

Last month, President Trump told Republicans in Texas and other states to redraw their congressional maps to help secure a Republican majority in the House of Representatives in the 2026 midterm elections: “Texas will be the biggest one. And that’ll be five.”

Republicans in the state legislature responded immediately. It is “absolutely permissible to draw maps on maximizing partisan advantage,” State Rep. Brian Harrison declared. Texas Democrats, vastly outnumbered in the legislature, tried to delay a vote in the special session called by Gov. Greg Abbott (R) by leaving the state, but the Republicans’ supermajority made the outcome inevitable.

“We have got to recognize the cards that have been dealt,” California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) announced, “and we have got to meet fire with fire.” To “offset the rigging of maps in red states,” Newsom called for a referendum to let California bypass its redistricting commission and create five more congressional districts favorable to Democrats.

Gerrymandering dates back to the 19th century, but it has intensified in recent decades due to residential self-sorting, software that can draw partisan maps with much greater precision, and now, apparently, a willingness to do it mid-decade for no special reason except partisanship, instead of only in years when the Census results come in.

In 2020, for example, Republicans and Democrats retained over 90 percent of their seats in the House. In 2024, only about 40 of the 435 seats in the House of Representatives were at all competitive.

Partisan gerrymandering subverts democracy by allowing a party to perpetuate its power in state legislatures and the U.S. House; by reducing incentives for politicians to be accountable to their constituents; by increasing loyalty to “the base,” who dominate low-turnout primaries (the only substantial threat to reelection); and by making bipartisan cooperation much less likely.

But a gerrymandering arms race may now be virtually impossible to stop.

In 2019, the Supreme Court, in a 5-4 decision, gave a green light to partisan gerrymandering. In his majority opinion in Rucho v. Common Cause, Chief Justice John Roberts acknowledged that partisan gerrymandering “might be incompatible with democratic principles,” but asserted that the case, which involved redistricting in North Carolina and Maryland, presented “political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts.”

Roberts maintained that remedies for partisan gerrymandering were in place, writing, “Numerous states are actively addressing the issue through state constitutional amendments and legislation placing power in the hands of independent commissions, mandating particular districting criteria for their mapmakers and prohibiting drawing districts for partisan advantage.” Article I Section 4 of the Constitution, Roberts added, gives Congress the authority to alter “time, place, and manner” regulations prescribed by a state “at any time.”

In a powerful and prescient dissent, Justice Elena Kagan noted that Roberts did not dispute claims that “if left unchecked,” partisan gerrymandering might “irreparably damage our system of government.” The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment applies to “the debasement or dilution of the weight of a citizen’s vote just as effectively as by wholly prohibiting the free exercise of the franchise,” Kagan asserted.

Kagan implied that Roberts’s assurances about existing remedies were either naive or disingenuous. Because politicians “maintain themselves in office through partisan gerrymandering,” she wrote, “the chances for legislative reform are slight.” Fewer than half of states allow voters to put referendums on the ballot. And Kagan cut the legs out from under Roberts’s observation that opponents of gerrymandering have recourse to state courts: “If they [state courts] can develop neutral and manageable standards to identify unconstitutional gerrymanders, why can’t we?”

To expand on this point, Kagan pointed out that every one of the 3,000 maps generated by an expert that adhered to all the criteria North Carolina used except partisan advantage led to at least one additional Democratic district over the initial Republican proposal. To the majority’s concern about the absence of concrete criteria for determining how much partisanship is too much, Kagan suggested that the appropriate answer was, “This much is too much. By any measure.” And the high court should have mandated that the state revise them.

In a recent YouGov poll, 76 percent of respondents (including 66 percent of Republicans) viewed partisan gerrymandering as unfair and deemed it a major problem. Only 4 percent thought it was not a problem at all. 74 percent of adults under 30 are concerned about partisan gerrymandering, up from 55 percent in 2022.

What recourse do we the people have? A tit-for-tat response, justified as a temporary suspension of principle, may well be the only option available to Democrats, even though Republicans will have an advantage if the war moves beyond just Texas and California. But it must be accompanied by a sustained response from large numbers of “ordinary” citizens, including visible and vocal manifestations of their urgent commitment to end a practice that, as Justice Kagan put it, turns “upside down the core American idea that all government power derives from the people … and enables politicians to entrench themselves in office.”

The goal would be persuading Democrats, Republicans and independents to make opposition to partisan gerrymandering a litmus test for who they vote for and against in 2025 and 2026.

And Trump’s announcement last week that he intends to lead a movement to get rid of mail-in ballots and voting machines gives added credence to the claim that nothing less than the future of free and fair elections is at stake.

Glenn C. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Emeritus Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.