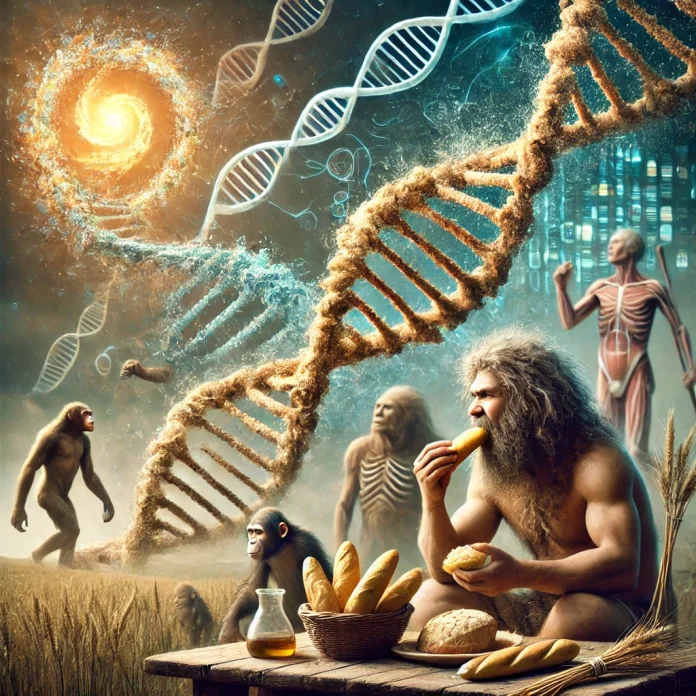

Your love for carbs like bread and chips might have deep roots in ancient DNA, according to new research.

Humans may have developed the ability to digest starchy foods, like bread and potatoes, long before the dawn of agriculture, and possibly even before diverging from Neanderthals. This is the conclusion of a recent study exploring how humans adapted to carbohydrate-rich diets.

Gene duplication, a type of mutation that results in extra copies of a gene, plays a key role here. For some time, scientists have known that humans carry multiple copies of a gene that begins the digestion of complex carbohydrates—like potatoes, rice, and certain fruits and vegetables—right in the mouth. The more copies of this gene, the better equipped a person is to break down starches.

However, until now, researchers struggled to pinpoint when and how this gene duplication occurred.

Led by the University of Buffalo (UB) and the Jackson Laboratory (JAX), the study found that the salivary amylase gene (AMY1)—which aids in starch digestion—likely duplicated much earlier than previously believed, as far back as 800,000 years ago, well before humans started farming.

Amylase, the enzyme produced by the AMY1 gene, breaks down starch into glucose and even contributes to the flavor of bread.

Professor Omer Gokcumen from UB’s Department of Biological Sciences, one of the lead authors of the study, explained: “The more AMY1 gene copies you have, the more amylase you can produce, which makes you better at digesting starch.”

The research analyzed genomes from 68 ancient human samples, including a 45,000-year-old sample from Siberia, and discovered that even pre-agricultural hunter-gatherers had multiple copies of the AMY1 gene. This means that early humans living across Eurasia were genetically prepared to digest starch-rich foods long before they began cultivating plants.

The study also identified AMY1 gene duplications in Neanderthals and Denisovans, suggesting this genetic change happened well before the human-Neanderthal split.

Kwondo Kim, a lead author from JAX’s Lee Lab, added: “This discovery pushes the origin of the AMY1 gene duplication back to over 800,000 years ago, much earlier than previously thought, and shows how this mutation helped humans adapt to dietary changes as starch consumption increased with new technologies and ways of life.”